Articles

Encyclopedia Judaica: Kurdistan

Edith Gerson-Kiwi / 1 ноября 2017 года

KURDISTAN, region in the Middle East, divided among three countries: *Turkey , *Iraq , and *Iran . The majority of the Muslim population of Kurdistan lives in Turkey, another part in Iran, and the smallest part in Iraq. In contrast, the Jews of Kurdistan – until their great exodus in 1950–51 – lived mainly in the Iraqi region (146 communities), some in the Iranian region (19 communities), and only a few in Turkey (11 communities). There were also a few Jews in the Syrian region and other places (11 communities). There are no accurate statistics on the Jews of Kurdistan. It has been estimated that before the establishment of the State of Israel there were between 20,000 and 30,000 Jews living there. Kurdish Jews also lived in the Diyala province of Iraq, especially in the town of *Khanaqin , the number of Jews varying between 1,689 in 1920; 2,252, 1932; and 2,851, 1947. The Jews of Mosul speak Arabic and some also understand Turkish and Kurdish. For this reason, some scholars do not reckon them among the Kurdish Jews, even though they resemble them somewhat in their way of life. They form a separate unit known by the name Miṣlawim.

In Iraq

HISTORY

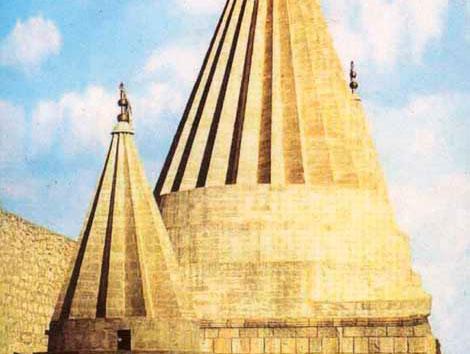

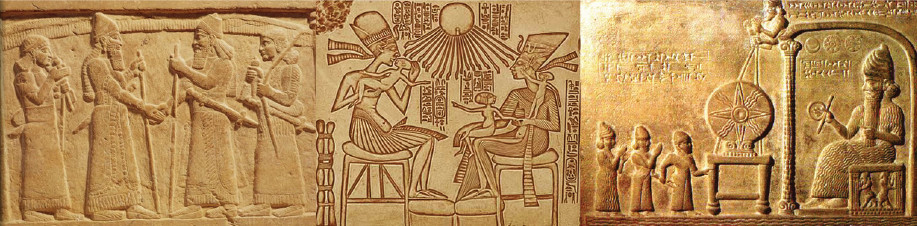

An ancient tradition relates that the Jews of Kurdistan are the descendants of the Ten Tribes from the time of the Assyrian exile. The first to mention this was R. *Benjamin of Tudela , the 12th-century traveler who visited Kurdistan in about 1170 and found more than 100 Jewish communities. In the town of *Amadiya alone, there were 25,000 Jews who spoke the language of the Targum (Aramaic) and whose numbers included scholars. The traveler *Benjamin the Second, who visited Kurdistan in 1848, also mentioned this tradition and added that the Nestorian (Assyrian) tribes were also descendants of the Ten Tribes and that they practiced Jewish customs. According to his assumption, they were descendants of Dan and Naphtali. There is no doubt that Halah and Ḥabor (modern Khabur), the river of Gozan (II Kings 17:6) – the places to which Shalmaneser, the king of Assyria, exiled the tribes – are in the vicinity of Kurdistan. During the Second Temple era the kingdom of *Adiabene was situated in this region; its inhabitants, together with their king, Monobaz, and his mother Helena, converted to Judaism in the middle of the first century. It may be presumed that there are descendants of these proselytes among the Jews of Kurdistan. *Onkelos translated Harei Ararat as "the mountains of Kardu" (Gen. 8:4); he also translated Mamlekhot Ararat as "the Kingdom of the land of Kardu" (Jer. 51:27). Josephus mentions the "mountains of Kurdukhim" (Ant. 1:93). In the Talmud it is related that "one accepts proselytes from the Kardus" (Yev. 16a).

An ancient popular tradition states that among the Assyrians of northern Iraq there were many families of Jewish origin and these were forcibly converted to Christianity more than 500 years ago. They still observe special Jewish customs, have not assimilated among the Christians, marry among themselves, and are afraid of revealing their origin in front of the Christians. Another popular tradition states that many of the descendants of the Ten Tribes who were exiled to this region by the kings of Assyria converted to Christianity. In 38 villages of Iraqi Kurdistan there were hundreds of Jews who claimed descent from the tribe of Benjamin and who possessed a holy book in Kurdish. They lived in the provinces of Mosul, Kirkuk, and Khanaqin. Some of them emigrated to *Afghanistan and the Caucasus. During the middle of the seventh century – at the time of the Arab conquest – the treaty of conquest was signed in the town of Dabil, on the Armenian border, with the "Magians [Zoroastrians] and the Jews" (according to al-Balādhurī, Futūḥ al-Buldān (1318 A.H.), 280; Yāqūt, Muʿjam, S.V. Dabīl). From this it is ascertained that there was another Jewish community in addition to that of Mosul and possibly that of Irbil.

During the 12th century two messianic movements arose in the neighborhood of the town of Amadiya: that of Menahem b. Solomon ibn Ruḥi (or Dugi) and that of David *Alroy . Some scholars regard these as one movement. There is no clear information available on the situation of the Jews during the 13th–15th centuries. From the beginning of the 16th century, however, information gradually becomes more available. The statistics provided by various travelers of different periods indicate great fluctuations over short periods of time in the Jewish population of every town and village. At times, the Jewish population increased or decreased by several hundred within four or five years. The cause for this was the instability of their economic and security situation; consequently, they often migrated from the smaller villages to the larger ones and from there to the large towns. Every pogrom caused the local Jews to flee to neighboring communities – for long or short periods – until the danger was past. In the 20th century the use of motor vehicles was an important reason for the removal of commerce from the smaller centers to the larger ones. Since there were no official statistics, the travelers relied solely on estimates.

The Jews under the British occupation (1917–21) enjoyed full rights of equality and freedom as well as a feeling of security. The majority of the Jews considered themselves as British citizens. Some grew rich, others were employed in the British administration, especially in Baghdad and Basra. They were interested in the continuation of British rule, and they expressed this in 1918, only a week after the armistice went into effect, when the Jewish community of Baghdad presented a petition to the civil commissioner of Baghdad, asking him to make them British subjects. Twice again, in 1919 and 1920, the Jews of Iraq appealed to the British high commissioner and asked him not to allow an Arab government to come to power or at least to grant British citizenship to the Jewish community en masse. The British authorities rejected this request, and the Jews were eventually appeased by personal assurances that ample guaranties would be afforded. However, when in April 1930 the League of Nations decided to adopt the mandate, the Jewish leaders decided to support the establishment of an Iraqi state under the British Mandate.

The Jews were given further assurances by Amir Faysal (1883–1933), who was the leading British candidate for the Iraqi throne. The new monarch-to-be made numerous speeches, including one before the Jewish community of Baghdad on July 18, 1921, one month before his coronation, in which he emphasized the equality of all Iraqis, irrespective of religion.

King Faysal continued to maintain cordial personal relations with individual members of the Jewish elite through his 12-year reign. As his first finance minister, he appointed Sir Sasson Heskel, the only Jew who ever held cabinet rank in Iraq. Four members represented the Jews in the Iraqi parliament. In 1946 their number increased to six. In the Senate Menahem Salih Daniel represented them and after him his son, EzraDaniel .

Because of their generally superior educational qualifications, Jews and Christians could be found in the civil service during the first decade of the kingdom while it was still under the British Mandate. However, as early as 1921, a strong Arab nationalist element rejected the employment of foreigners and non-Muslims. This opposition intensified after Iraq had gained full independence in 1932 and became even stronger after the death of Faysal the following year.

Iraqi Jews did not know the kind of antisemitism that prevailed in some Christian states of Europe. The first attempt to copy modern European antisemitic libels was made in 1924 by Sādiq Rasūl al-Qādirī, a former officer in the White Russian Army. He published his views, particularly that of worldwide conspiracy, in a Baghdadi newspaper. The Jewish response in its own weekly newspaper, al-Misbah, compelled al-Qādirī to apologize, although he later published his antisemitic memoirs.

At that time the press drew a clear dividing line between Judaism and Zionism. This line became blurred in the 1930s, along with the demand to remove Jews from the genealogical tree of the Semitic peoples. This anti-Jewish trend coincided with Faysal's death in 1933, which brought about a noticeable change for the Jewish community. His death also came at the same time as the Assyrian massacre, which created a climate of insecurity among the minorities. Iraqi Jewry at that time had been subject to threats and invectives emanating not only from extremist elements, but also from official state institutions as well. Dr. Sāmī Shawkat, a high official in the Ministry of Education in the pre-war years and for a while its director general, was the head of "al-Futuwwa," an imitation of Hitler's Youth. In one of his addresses, "The Profession of Death," he called on Iraqi youth to adopt the way of life of Nazi Fascists. In another speech he branded the Jews as the enemy from within, who should be treated accordingly. In another, he praised Hitler and Mussolini for eradicating their internal enemies (the Jews). Syrian and Palestinian teachers often supported Shawkat in his preaching.

The German ambassador, Dr. F. Grobba, distributed funds and Nazi films, books, and pamphlets in the capital of Iraq, mostly sponsoring the anti-British and the nationalists. Grobba also serialized Hitler's bookMein Kampf in a daily newspaper. He and his German cadre maintained a great influence upon the leadership of the state and upon many classes of the Iraqi people, especially through the directors of the Ministry of Education.

The first anti-Jewish act occurred in September 1934, when 10 Jews were dismissed from their posts in the Ministry of Economics and Communications. From then on an unofficial quota was fixed for the number of Jews to be appointed to the civil service.

Pro-Palestinian, anti-British, anti-Jewish, and anti-Zionist sentiments rose to new heights in Iraq in 1936. The Arab general strike and the revolt, which erupted in Palestine that year, gave the conflict a new centrality in Arab politics. The atmosphere in Baghdad became highly charged. The Committee for the Defense of Palestine circulated anti-Jewish pamphlets. Over a four-week period, extending from mid-September to mid-October, three Jews were murdered in Baghdad and in Basra. A bomb, which however failed to explode, was thrown into a Baghdadi synagogue on Yom Kippur (September 27). Several other bombs were thrown at Jewish clubs, and street gangs roughed up a number of Jews.

The president of the Baghdadi Jewish community, Rabbi Sassoon Kadoorie , who was himself a staunch anti-Zionist, issued a public statement, in response to a demand from the national press, affirming loyalty to the Arab cause in Palestine and dissociating Iraqi Jewry from Zionism. This did not bring about any real improvement in the situation and, in August 1937, incidents against the Jews were renewed, fostered then and later by Syrians and Palestinians who had settled in Iraq.

THE ANTI-JEWISH POGROM OF JUNE 1-2 1941- "ALFARHUD"

On June 1, the first day of Shavuʿot, which in Iraq was traditionally marked by joyous pilgrimages to the tomb of holy men and visits of friends and relatives, the Hashemite regent, 'Abd al-Ilāh, returned to the capital from his exile in Transjordan. A festive crowd of Jews crossed over the west bank of the Tigris River to welcome the returning prince. On the way back, a group of soldiers, who were soon joined by civilians, turned on the Jews and attacked them, killing one and injuring others. Anti-Jewish riots soon spread throughout the city, especially on the east bank of the Tigris, where most of the Jews lived. By nightfall, a major pogrom was under way, led by soldiers and paramilitary youth gangs, followed by a mob. The rampage of murder and plunder in the Jewish neighborhoods and business districts continued until the afternoon of the following day, when the regent finally gave orders for the police to fire upon the rioters and Kurdish troops were brought in to maintain order.

In the " Farhud," 179 Jews of both sexes and all ages were killed, 242 children were left orphans, and 586 businesses were looted, 911 buildings housing more than 12,000 people were pillaged. The total property loss was estimated by the Jewish community's own investigating committee to be approximately 680,000 pounds.

The " Farhud " dramatically undermined the confidence of all Iraqi Jewry and, like the Assyrian massacres of 1933, had a highly unsettling effect upon all the Iraqi minorities. Nevertheless, many Jews tried to convince themselves that the worst was over. A factor in this was the commercial boom during the war, of which the Jewish business community was the prime beneficiary. Another factor was the tranquility which prevailed during the next years of the war. But the shadow of the " Farhud " continued to hover for years.

The pogrom caused a split between the youth of the Jewish community and its traditional leadership. The new generation turned to two separate directions: the Communist and the Zionist movements, the activity of both being underground.

THE ZIONIST UNDERGROUND

The Zionist Movement renewed its activity in March 1942 by forming the youth organization called Tenu'at he-Ḥalutz (the Pioneer Movement) and paramilitary youth, Haganah, among Iraqi Jews. Contrary to the Communist underground, the Zionists did not work against the regime. They concentrated on teaching Hebrew and educating the young generation to Zionism and pioneering. A main purpose was to convince the Jews, mainly the youth, to immigrate to Ereẓ Israel.

The ranks of the Zionist movement in Iraq increased when World War II was over, and the Iraqi press began to address the Palestine question. The Zionist underground organizations in Iraq, despite some crises, were flooded, from 1945 until 1951, with requests for joining. The most dangerous crisis was that of October 1949, which nearly wiped out the Zionist movement in Iraq. The Iraqi authorities arrested about 50 Jews who were accused of Zionism and court-martialed. The second crisis was that of May–June 1951. When the evacuation of the Jews was nearing its end, the Iraqi government uncovered a spy ring in Baghdad, run by two foreigners, Yehuda Tajir and Rodny, who were arrested. The authorities also discovered explosives, guns, files, typewriters, presses, and membership lists hidden in synagogues or buried in private homes. As a result, the police arrested about 80 Jews, 13 of them were sentenced to long terms of imprisonment, two others (Yosef Basri and Shalom Saleh) were sentenced to death and hanged on January 19, 1952. By June 15, 1951, the order was given to the Zionist underground to cease its activity in Iraq.

OFFICIAL ANTI-SEMITISM

When World War II was over the former pro-Nazi followers were released and began anew their activities and incitement against the Jews. The General Assembly vote in favor of the partition of Palestine on November 29, 1947, increased tensions between Arabs and Jews in Iraq and the authorities started to oppress the Jews.

The declaration of martial law, before sending Iraqi troops to Palestine, marked the beginning of official antisemitism. At first it was directed mainly against Communists but soon was used against Jews, when it became clear that the Arab offensive in Palestine was encountering serious difficulties. Now the Iraqi authorities seemed increasingly willing to accommodate anti-Jewish demands as a mean of diverting the attention of the Iraqi population from the failure in Palestine and from concern with social and political reforms. From now on, abuses and restrictions characterized the life of the Jews in Iraq. Restrictions were imposed on travel abroad and disposal of property. Hundreds of Jews were dismissed from public service; efforts were made to eliminate Jews from the army and the police; they were prohibited from buying and selling property; they were also discriminated against in obtaining the necessary licenses granting access to some professions.

At the same time the nationalist press opened with aggressive attacks against the Jews, practically daily. The longstanding distinction between Judaism and Zionism was fast becoming blurred, The Jews were held responsible for the economic hardship faced by Iraq in 1948–49, and their leaders were threatened by the national press. The most important effect, which shook the Jewish community to the core, was the hanging of Shafiq Adas, one of the wealthiest Jews in the country, in front of his house in Basra on September 23, 1948. Adas was condemned on the unlikely charge of having supplied scrap metal to the Zionist state.

When Adas was executed about 450 Jews were in the jails; added to these were those arrested the following year, in early October 1949. The detainees were sentenced to terms of imprisonment ranging from 2 to 10 years. In carrying out the arrests the police also arrested another 700 Jews and released them after investigation, most of them were relatives of those who were brought before martial courts.

THE JEWISH EXODUS - OPERATION EZRA & NIHEMIAH (1949)

Throughout 1949, the general disaffection of Iraqi Jewry was exacerbated. With this atmosphere Jewish youths were fleeing the country. The clandestine crossing of the Iranian border began to assume major proportions. Within a few months in 1950, about 10,000 Jews fled Iraq in this way. Once in Iran, most Iraqi Jews were directed to the large refugee camp administered by the Joint Distribution Committee near Teheran, and from there they were airlifted to Israel.

In an attempt to stabilize the situation and to solve the Jewish problem, the government introduced a bill in the Iraqi Parliament at the beginning of March 1950 that would in effect permit Jews who desired to leave the country for good to do so after renouncing their Iraqi citizenship. The bill also provided for the denaturalization of those Jews who had already left the country. The bill was duly passed in the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate as Law No. 1 0f 1950.

Iraqi government officials thought that only about 6,000–7,000 and at most 10,000 Jews would take advantage of the new law. The British diplomats in Baghdad and the Israelis shared this view as well. They were all mistaken. The Jews were tired of life in Iraq. And when the Zionist organization in Iraq issued a call at the end of Passover (April 8, 1950) for Jews to come forward and register for emigration in the centers which had been set up at the major synagogues, the call was highly effective. The overwhelming majority of the Jewish community preferred to leave their birthplace. By July 5, 1951, about 105,000 had arrived in Israel.

On March 10, 1951, only one day after the registration deadline had passed, while nearly 65,000 Jews were waiting for departure, the authorities enacted a law which froze the assets of all departing Jews and placed them under the control of a government bureau. Parliament passed a second law, which declared that those Iraqi Jews who were abroad and did not return home within a specific period would forfeit both their nationality and their property. Although some individuals succeeded in smuggling out some money after March 10, 1951, many more were reduced to paupers, being allowed to take out only 50 dinars ($140) per adult and 20 to 30 dinars ($56 to $84) per minor, depending upon the age.

About 6,000 Jews preferred to remain in Iraq after the mass emigration. Over the years this number fell to about 4,700 in 1957 and about 3,000 in 1968 when the Baʿth Party came to power in Iraq. Their number continued to decline and in the early 21st century there were only a handful of Jews still living in Iraq. Most of those remaining were from the elite and the rich families, who believed that the violent storm which had marked the life of the Jews in Iraq before and during the mass emigration would pass.

The Jewish community, which consisted before the mass emigration of about one quarter of the population of Baghdad, now became a small and unimportant one. These Jews no longer dominated the economic and the financial life of the country, and Jewish youth posed no danger to the regime through activities in the communist underground. So the regime removed some of the restrictions, and the pressure upon them was lightened to some degree. But in principle, the antagonistic attitude to them remained. Still in force were the restrictions on Jews registering in the universities and the sanction of taking away Iraqi nationality from those who did not return to the country within a limited time, which was marked in their passports. In 1954 the authorities nationalized the Jewish Meir Elias Hospital, which was the most modern and largest in Iraq. The Iraqi government also expropriated from the Jewish community the Rima Kheduri Hospital, which treated eye diseases.

Relief came under Brigadier 'Abd al-Karīm Qāsim (1958–1963), who toppled the monarchy by a military revolution on July 14, 1958. Qāsim canceled all the restrictions against the Jews. He also released Yehuda Tajir and let him go back to Israel. The Jewish golden age under Qāsim was affected however by the confiscation and destruction of the Jewish cemetery, located in the middle of the capital, in order to build a tower to immortalize his name.

Qāsim was assassinated by Colonel 'Abd al-Salām 'Ārif, who carried out a successful coup on February 13, 1963. The new rulers reinstated all the restrictions which had been in force before Qāsim, and added others: Passports were not to be issued to Jews; the Jews were prevented from discounting their promissory notes and it was prohibited to grant them credit in the then-nationalized banks; again, Jewish students were not to be admitted to government colleges; a warning was issued to all Jews abroad to return to Iraq within three months, otherwise they would be denationalized and their movable and immovable property in Iraq would be sequestrated; Jews were not allowed to sell their landed property.

After the Six-Day War, the situation of the Iraqi Jews worsened more. They were terrorized and cruelly persecuted. The government opened with a series of detentions, enacted laws, and issued instructions which brought the Jewish community to the threshold of starvation. The measures taken against the small isolated Jewish community of Baghdad after the Six-Day War included: warning the public not to cooperate with them; expelling them from all social clubs; depriving Jewish importers and pharmacists of their licenses; forbidding all transactions with Jews (including access to the banks); prohibiting them from selling their cars and furniture; and cutting off all telephone communications from their homes, offices, or stores.

Under the Baʿth regime (1968–2003), persecution increased and many Jews reached starvation level. Some were jailed, accused of spying or held without any formal charge. Within one year (January 1969–January 1970), 13 were hanged; up to April 1973 the total number of Jews hanged, murdered, kidnapped, or who simply disappeared reached 46; dozens more were jailed.

The shock following the executions of the innocent Jews caused repercussions throughout the world and the world conscience was aroused. The Iraqi government responded to the world reaction by relaxing, for a while, some of its anti-Jewish discriminatory measures, including those limiting travel in Baghdad and throughout Iraq, too. At the same time a peace treaty was signed (March 1970) between the Iraqi government and the Kurdish rebels. Some Jews seized the opportunity and escaped across the Kurdish Mountains, in the summer of 1970, to the Iranian frontier. Up to 300 Jews fled the country in this way. In September 1971 the authorities began to issue passports to the Jews, and about 1,300 Jews left Iraq legally. They sought refuge mainly in England, Canada, the United States, and Israel. In 1975 the Jews in Iraq numbered about 350; over time this figure declined further, reaching c. 120 in 1996. At the beginning of the 21st century, as stated, there were only a handful of Jews there. Thus came to its end the most ancient Diaspora of the Jewish people.

ECONOMIC CONDITIONS

The economic situation of the Jews was difficult; many of them lived in poverty and distress. The urban Jews were essentially engaged in commerce and crafts. Several of them owned estates with peasants and agricultural laborers. In eastern Kurdistan the number of merchants was greater than that of craftsmen. These tradesmen could be divided into wholesalers, shopkeepers, and peddlers. The craftsmen were weavers, gold- and silversmiths, dyers, carpenters, tanners, cobblers, and unskilled workers. There were no bankers among the Jews, this occupation being in the hands of the feudal lords. The Jewish farmers cultivated mainly wheat, barley, rice, sesame, lentils, and tobacco. They owned orchards, vineyards, flocks of sheep, and herds of cattle. There were also agricultural villages, all of whose inhabitants were Jews (e.g., Sindur). Jewish peasants were found mainly in *Ruwandiz , Tel-Kabar, Barazan, *Dehok , Aqrah, Shandukha, Bitanura, Bashkala, Koi-Sanjaq, Mirawa, Karada, and Girzengal. As a result of droughts, famines broke out in several places (1880, 1888, 1889, etc.) and their inhabitants were compelled to migrate to other places. Many fled to Baghdad, where they found employment in various occupations. The Jews of Kurdistan are known for their strength and sturdiness.

INSTABILITY OF LIVING CONDITIONS

The lives of the Jews of Kurdistan were subject to anarchy. Political and economic factors determined their places of residence and their migrations from one place to another. They were scattered in many villages and lived among various Muslim and Christian sects. Robbery and murder were common occurrences. Because of their isolation from the outside world, no concern was shown for them; their persons and belongings were enslaved to feudal rulers. In order to safeguard their lives, they were compelled to seek the protection of the powerful Agha, to whom they paid a special tax. He was a kind of tribal chief who traveled about accompanied by groups of armed servants. The Jews subordinated themselves to him and fulfilled his orders. Some of the Aghas sold Jews or gave them away as presents; this servitude continued until the beginning of the 20th century. In 1912, 12 Jews were murdered in Kurdistan. For them this was the sign to liquidate their affairs and sell their fields and houses at a low price in order to emigrate to Palestine. The anti-Zionist propaganda which began in Iraq in 1925 adversely affected the position of the Jews of Kurdistan. The persecutions gained in intensity from day to day and reached their height at the time of the revolt of Rashīd ʿĀlī (1941). With establishment of the State of Israel, most of them traveled to Baghdad and from there flew to Israel in the "Operation Ezra and Nehemiah." In 1970 a small number of Kurdish Jews remained in the regions of Iran, Turkey, and Syria.

THE ORGANIZATION OF THE COMMUNITIES AND THEIR SPIRITUAL FOUNDATION

Prior to the 19th century the large communities were headed by nesi'im who imposed their authority on the public and collected special taxes. The nasi was also called shoter ("officer of the law") or sar ("minister"). The ḥakhamim were also subordinated to them. This position was abolished during the 19th century. From the beginning of the 16th century, there were several rabbis of the Adoni (or *Barazani ), Mizraḥi, Duga, and Ḥariri families. Some of them practiced practical Kabbalah and various legends were woven around them. About 30 Kurdish paytanim are known from among the inhabitants of Barazan, Mosul, Amadiya, Ḥarīr, Naṣībīn, *Zākho , and other places. They wrote religious and secular poems in Hebrew and in Aramaic; 54 of them were published by Abraham Ben-Jacob in his book Kehillot Yehudei Kurdistan (1961). The most important of these poets were R. Samuel b. Nethanel ha-Levi *Barazani , who was also a rosh yeshivah in Mosul during the 17th century, and his daughter Asenath; R. Phineas b. R. Isaac Ḥariri and his son R. Ḥayyim; R. Simeon b. Jonah Mizraḥi; R. Gershon b. Raḥamim; R. Simeon b. Benjamin Abidani; R. Moses b. Isaac Bajulnaya; R. Samuel b. Simeon ʿAjamiya; R. Baruch b. Samuel Mizraḥi, the author of Shirei Zimrah; and others.

Each community was headed by the ḥakham, who was also a ḥazzan, mohel, shoḥet, and bodek ("examiner of slaughtered animals"), treasurer, teacher, scribe, and writer of amulets. The smaller communities were subordinated to the larger ones; in all religious and legal matters they turned to the rabbis of Baghdad. Religious and spiritual life was centered around the synagogue and the talmud torah. In the large communities there were several synagogues, some of which were very old. One was built in 1210 (in Mosul) and a second in 1228 (in Amadiya). The Alliance Israélite Universelle opened schools only in the towns of Mosul (1900 and 1906) and Kirkuk (in 1912).

KURDISH LANGUAGE

The Jews of Kurdistan spoke an Aramaic with insertions of Turkish, Persian, Kurdish, Arabic, and Hebrew words. They called it the "language of the Targum" or Lishna Yehudiyya ("language of the Jews"), as well as Lashon ha-Galut. The Arabs called it jabalī, i.e., "of the mountains," because it was essentially spoken by the inhabitants of the mountains. They called themselves Anshei Targum("People of [the language of] the Targum"). A.J. Maclean found four dialects in the language; J.J. *Rivlin found only three dialects. The Nestorian Christians who live in this region also speak Aramaic, which they refer to as "Syrian." This language is also spoken by the Sabeans, who live along the banks of the Lower Euphrates, around the town of Nāṣiriyya, and along the banks of the Lower Tigris in the region of Amadiya. In about 1930 it was estimated that 9,837 persons spoke *Aramaic in Iraqi Kurdistan; they were to be found in the following provinces (qaḍāʾ): Zakho (1,471), Amadiya (1,821), Zibar (100), Ruwandiz (250), Dehok (843), ʿAqrah (1,000), Irbil (250), Matuk (1,900), Koi-Sanjaq (302), Sulaimaniya (900), Halabja (400), and in others (500). In addition to the above, Aramaic was also spoken in Persian and Turkish Kurdistan and in Israel. It is estimated that between 15,000 and 20,000 people speak Aramaic.

ALIYYOT TO PALESTINE

Dozens of emissaries from Palestine visited Kurdistan; they noted the Jews' sympathy for and contributions to the Holy Land. The aliyah to Palestine already began during the 16th century. The first immigrants lived in Safed. Between 1920 and 1926, 1,900 Kurdish Jews emigrated to Palestine. In 1935, 2,500 Jews emigrated. With the establishment of the State of Israel almost all the Jews of Iraqi Kurdistan (see *Iraq , Kurdish Jews), and many from other places, emigrated there. In Israel they formed committees, according to the provinces and towns where they had lived in Kurdistan, and are scattered in many towns and settlements, with a large proportion living in and around Jerusalem.

[Abraham Ben-Yaacob]

The Kurdish Parliament passed new laws in May 2015 which established government departments dealing with seven religious minorities in their region, including the Baha'i, Zoroastrians, Yazidis, and Jews. Sherzad Omer Mamsani was named the Jewish Affairs Representative in Kurdistan in late 2015, with the job of showing hospitality to local Jews and fostering positive relations with Israel and Jewish people worldwide. Mamsani was placed in charge of all Jews of Kurdish origin, whom number close to 300,000 and mostly reside in Israel.

In Iran

The Jewish Kurds of Iran have traditionally been living in Iran since 722 B.C., when according to II Kings (17:6; 18: 9–12) they were deported from Samaria and brought to the cities of the Medes, which roughly correspond to the present provinces of *Azerbaijan , Kurdistan, and the western part of *Gilān . Jewish Kurds are mentioned by Benjamin of Tudela. The Jewish Kurds of Iran speak their own language, which linguistically is classified as a Neo-Judeo-Aramaic language. They have produced their own literature in this language. It is close to the present language of the Assyrians (Ashuri). If their language is an indication of their ethnic identity, one may say they do not live only in the province of Kurdistan but also in the cities and villages of Azerbaijan and territories adjacent to Gilān, *Hamadan , *Kermanshah , and their vicinity. As such, it is safe to say that in the 20th century they lived in more than 45 towns and villages in north and northwest Iran.

There are no coherent historical records of their past except some scattered information gathered from Jewish and non-Jewish travelogues. Rabbi David d'Beth Hillel visited the following settlements of the Iranian Jewish Kurds around 1827/28: Bāneh, where ten Jewish families lived together with 1,000 Muslim families; they were poor and possessed one synagogue. Fifteen Jewish families lived in Saqqez which had 1,000 Muslim families. They had one synagogue and some of them were wealthy. Sāvoj-Bulāgh (today called Mahābād) was a large city, having 25 Jewish families and a fine synagogue. They were generally rich and lived among 15,000 Muslim families. R. David mentions a village where 10 Jewish families lived but he does not give its name (most probably the village was Tāzeh-Qal`eh). In Urmiah (name changed to Rezāiyeh) 200 Jewish families lived among 60,000 Muslims who, according to the traveler, were "wicked" and spoke Persian, Turkish, and Kurdish. Jews had three synagogues and most of them lived comfortably. The rabbi of the Jewish community was a rich man. The Christians there were more mistreated than the Jews. The "beautiful city" of Salmās (changed to Shāhpur) had 100 Jewish and 400 Christian families and 10,000 Muslim inhabitants. Most of the Jews were rich. They had one fine synagogue. In the city of Bāsh-Qal'eh there lived 20 Jewish, 100 Christian, and 2,000 Muslim families. Most of the Jews were rich and they had one small synagogue. In the small town of Miyāndoab there were 15 Jewish families among 4,000 Muslims. The town had no Christians. In 1801 a violent pogrom befell the Jews of the city as a result of a blood libel. The town of Garus had 25 Jewish families living among 3,000 Muslim families. Some of the Jews were rich. There were no Christians in the town. In the big city of Seneh (name changed to Sanandaj) there were 300 Jewish families among 50,000 Muslim families. They had two synagogues and some were rich merchants. In the small town of Qoslān five Jewish families lived among 1,000 Muslims. No Christians lived there.

There is no doubt that there were several dozen towns and villages where Jewish Kurds lived. Reports about some of them came before their immigration to the State of Israel. In addition to what has been mentioned above, we hear of towns and villages such as Bijār, Bukān, Gahvāreh, Marivān, Naqdeh, Oshnoviyeh, Qorveh, Sardasht, Shāhin-Dez, Soldoz, Takāb, and others. In 1948, the Jewish Agency in Teheran estimated the total number of Jewish Kurds in Iran, Iraq, and Turkey at about 50,000, of which about 15,000 lived in Iran. It is possible that the real figures were higher. Almost all of them were preparing themselves for aliyah to the Jewish State. In general, relative to other Jewish communities across Iran, Jewish Kurds had correct relations with the Muslims, particularly with the Sunnis. The Israel-Arab conflict aggravated their fragile relations, however. By the end of the 20th century a small number of Jews were reported to have been living in large cities of Kurdistan such as Sanandaj and Mahābād. In Israel, the Jewish Kurds of Iran separated themselves from those of other countries. They have their separate organizations and even plan their feast on the last day of Passover on different days and under different names: Seyrānah for the Kurds of Iran and Sahrānah for other Jewish Kurds. Their common periodical in Israel is called Hitḥadshut.

The economic boom of the 1960's and the 1970's in Iran benefited the Jews too. Many Jews became rich, which enabled them to provide higher education for their children. In 1978 there were about 80,000 Jews in the country, constituting one-quarter of one percent of the general population. Of these Jews, 10 percent were very rich, the same percentage were poor (aided by the Joint Distribution Committee) and the rest were classified as from middle class to rich.

Approximately, 70 out of 4,000 academicians teaching at Iran's universities were Jews; 600 Jewish physicians constituted six percent of the country's medical doctors. There were 4,000 Jewish students studying in all the universities, representing four percent of the total number of students. Never in their history were the Jews of Iran elevated to such a degree of affluence, education, and professionally as they were in the last decade of the Shah's regime. All this changed with the emergence of the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI).

It is estimated that during the first 10 years of the Islamic regime about 60,000 Jews left Iran; the rest, some 20,000, remained in Teheran, Shiraz, Isfahan, and other provincial cities. Of the 60,000 Jews who emigrated, about 35,000 preferred to immigrate to the U.S.; some 20,000 left for Israel, and the remaining 5,000 chose to live in Europe, mainly in England, France, Germany, Italy, or Switzerland. The spread of the Iranian Jews in the U.S. provides us with the following demographic map: of the total 35,000, some 25,000 live in California, of whom about 20,000 prefer to dwell in Los Angeles; 8,000 Iranian Jews live in the city of New York and on Long Island; the remaining 2,000 live in other cities, mainly in Boston, Baltimore, Washington, Detroit, or Chicago.[Amnon Netzer (2nd ed.)]

Musical Tradition

The style of Jewish music in Kurdistan is conditioned by the multinational and multilingual character of the country which in its long history scarcely ever aimed at a cultural centralization and thus helped to preserve the musical dialects of the Iraqi, Iranian, Syrian, and Turkish regions of the area. The foremost feature of Jewish song in Kurdistan is the unique melodic style of the renditions of Aramaic texts (which is distinct from the general "Oriental Sephardi" style used for Hebrew texts). Connected with liturgical or spiritual texts, this melodic style is basically determined by the speech-melody of the Aramaic language, with a tendency to proceed over long stretches in a litany or parlando style, especially if the text is of a narrative nature (as in the chanting of the biblical books in the local Aramaic version, or the Zohar). If the contents are of a poetical or meditative-kabbalistic nature, the words may be interrupted by long and drawn-out melismatic insertions produced in a slow and deep vibrato, often with a curious change of voice timbre.

A further factor for the formation of Jewish song in Kurdistan is the contact with Arab music, which since the early days of Islam had gradually replaced the older musical idiom of the Mesopotamian area, especially in the sphere of artistic urban music. Equally important for the formation of the Jewish-Kurdish style of synagogue song were the bonds with the major tradition of Jewish music, foremost – cantillation and ḥazzanut styles. These were brought in and taught by emissaries from the spiritual centers of Near-Eastern Judaism, in the "Oriental Sephardi" idiom which was in itself already a synthesis, and which is different from the indigenous "mountain" (jabalī) idiom. The Kurdish cantors thus tended to be musically bilingual. However, time works against the continuation of the indigenous tradition.

Still another factor is the Kurdish folk song proper, in the Kurmanji language, with its epics, ballads, and dances, which has been widely accepted by the Jews, and synthesized with their other singing styles. The fact that Kurdish Jews lived as free peasants side by side with their Muslim neighbors is a rare instance in the history of Diaspora life, and has doubtlessly contributed to the acceptance of the host culture's lore and song.

Summarizing the distribution of languages and musical structures, which exists even within the boundaries of the one (and main) region of Iraqi Kurdistan, the following divisions become apparent in which the distinction of language is congruent with the distinctiveness of musical style: (1) Hebrew, for the liturgical music of the synagogue; (2) "Targum," i.e., Aramaic, for the religious and paraliturgical music of the ḥeder, yeshivah, and some rituals, serving for the study, vernacularization, and paraphrasing of the sacred texts; (3) Arabic, for the secular songs taken over from popular and artistic urban music, serving for purely social gatherings; and (4) Kurdish (Kurmanji), for the folk tradition of heroic epics, ballads, and dances of the rural milieu. The Hebrew and Aramaic idioms belong to the cycle of the liturgical year and the religious life cycle, and the Arabic and Kurdish idioms belong to the social folk level functions.

In this abundance of structures some main classes of music deserve particular attention. First is the chanting of the Bible, which has always been the nucleus of all creative imagination in Jewish music and its main contribution to the world's music culture. One of its basic forms is the chanting of the Psalms in a kind of speech-melody oscillating around an (imaginary) tone axis, which closely follows the poetical structure of the two half-verses, marking the main divisive points with definite and distinct melodic turns. The elaborate system of the masoretic accents is not utilized, and it is likely that an earlier version has been preserved here. Similar archaic trends can be observed in the melodic patterns of the cantillation of the biblical prose books, which suggest a pre- or extra-masoretic jabalī tradition for the "mode of the Prophets." The most ingenious part of Kurdish-Jewish song tradition is the paraphrasing of biblical stories in epic form, in the Aramaic vernacular. Its melodic frame reveals many common traits with the cantillation of the Pentateuch.

Источник: jewishvirtuallibrary.org