Articles

The Genocide of Yazidis is Not Over

Liz Olson / 1 августа 2017 года

The women and girls victimized by IS deserve to see their persecutors held accountable for their crimes in an international court.

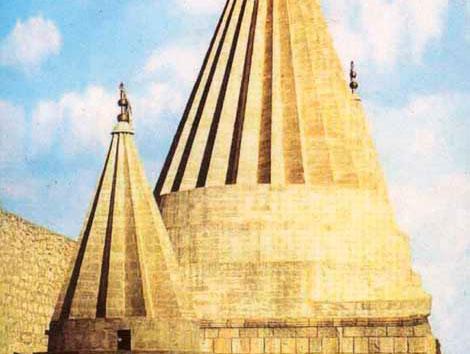

On August 3, 2014, Islamic State (IS) fighters attacked the Yazidi community in Sinjar, Iraq. Since then, the Yazidis have been the target of an explicit and ongoing genocidal campaign to destroy their people and their culture. Despite recognition from the international community that genocide is occurring, there has not been a concerted effort to halt this ethnic cleansing and save the thousands of Yazidi women and girls still held captive by IS.

As part of its offensive three years ago, IS attacked and massacred thousands of Yazidis in the town of Sinjar. “For those Yazidi who didn’t make it to [safety] and who weren’t close enough to the Kurdish regions to flee, they found themselves encircled by [IS],” says Sareta Ashraph, the former chief analyst of the UN Commission of Inquiry on Syria. “And the crimes that were committed against them and in many cases are still being committed against them depended primarily on the sex of the victim, the gender of the victim and secondarily the age of the victim. For that reason the Yazidi genocide is instrumental in understanding the role gender plays in the crime of genocide.”

The failure of the international community to intervene in the Yazidi genocide reflects the immense gap between states’ obligation to respond to genocide and their lack of action to intervene. While states have a legal obligation to act to prevent and punish genocide, the parameters of that obligation are ambiguous. All states with a “capacity to influence” the perpetrators of genocide are obligated to act, but the breadth of this mandate fails to identify exactly who is obligated to act and what actions they must take. At a recent high-level meeting about international laws on genocide, legal experts agreed there must be legal clarity on the duty to prevent and suppress genocide for the conventions to be effective.

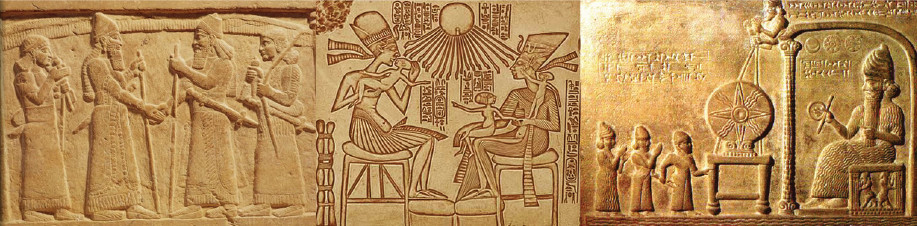

Part of the issue is that the Genocide Convention was written at a time when nation states were the main actors both perpetrating and responding to genocide. This outmoded state-based framework is ill suited to address the realities of modern conflict involving atrocities committed by non-state actors.

In response to modern terrorism and the rise of groups like IS, new treaties on terrorism and organized crimes have been developed that provide models for how international laws can grapple with the realities of today’s conflicts. Genocide experts agree that there is value in learning from and adapting some of the effective methods of response developed under the global counterterrorism framework and applying them to the Genocide Convention.

Another barrier to effective international action to prevent and prosecute genocide is the common misconception that genocide is measured in mass killings and mass graves. During the attack on Sinjar, IS fighters executed male Yazidis, leaving the women and children to be systematically abducted and enslaved. Ashraph explains: “The understanding of the Yazidi genocide comes primarily from women, because they are the living victims.”

The Genocide Convention defines four non-killing crimes of genocide: preventing births within the group; separating children from their families; denying basic necessities such as food and water; and inflicting physical or mental harm, including through torture and rape. These crimes primarily target women and have rarely been prosecuted.

Today, the Islamic State is committing all four of these crimes against the Yazidi community with the intent to destroy the ethnoreligious minority. “Genocide is primarily a crime of intent, rather than of scale and it [is] the intent that transforms a series of conduct into a genocidal act,” says Ashraph. Addressing these gendered non-killing crimes of genocide is essential to effectively intervening to stop the genocide and prosecute those responsible.

“This is a genocide which could still be successful,” Ashraph warns, “this is a crime that is still continuing.” On the third anniversary of the IS attack on Sinjar, over 3,000 Yazidi women and children remain in captivity.

Almost 70 years after the Genocide Convention was adopted unanimously by the United Nations General Assembly, it is time to prioritize its implementation. This means opening a discussion with a range of actors, including human rights lawyers and military leaders, about the intersection between human rights and counterterrorism, and the relationship between gender and genocide. The women and girls victimized by IS deserve to see their persecutors held accountable for their crimes in an international court.

Источник: fairobserver.com