Articles

Who Are the Yazidis, the Ancient, Persecuted Religious Minority Struggling to Survive in Iraq?

Avi Asher-Schapiro / 11 августа 2014 года

The U.S. contemplates sending military aircraft and possible ground troops to rescue the Yazidis, as more American military advisers arrive in Iraq to help plan an evacuation of the displaced people.

For their beliefs, they have been the target of hatred for centuries. Considered heretical devil worshippers by many Muslims—including the advancing militants overrunning Iraq—the Yazidis have faced the possibility of genocide many times over. Now, with the capture of Sinjar and northward thrust of extremists calling themselves the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant, or ISIL (also known as the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria, or ISIS), Iraq's estimated 500,000 Yazidis fear the end of their people and their religion. In less than two weeks, nearly all the Yazidis of Sinjar have fled north, seeking refuge in Kurdish territory, while thousands remained trapped in the rugged Sinjar mountains, awaiting rescue. "Sinjar is (hopefully not was) home to the oldest, biggest, and most compact Yazidi community," says Khanna Omarkhali, a Yazidi scholar at the University of Göttingen. "Extermination, emigration, and settlement of this community will bring tragic transformations to the Yazidi religion," she adds.

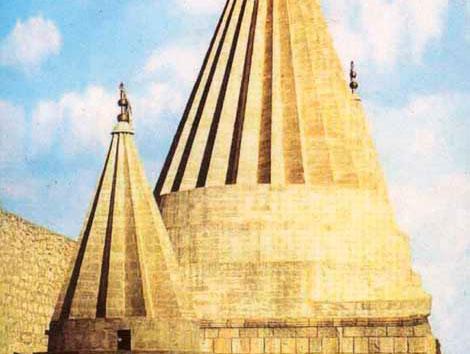

The Yazidis have inhabited the mountains of northwestern Iraq for centuries, and the region is home to their holy places, shrines, and ancestral villages. Outside of Sinjar, the Yazidis are concentrated in areas north of Mosul, and in the Kurdish-controlled province of Dohuk. For Yazidis, the land holds deep religious significance; adherents from all over the world—remnant communities exist in Turkey, Germany, and elsewhere—make pilgrimages to the holy Iraqi city of Lalesh. The city is now less than 40 miles from the Islamic State front lines.

As the Islamic State continues to swallow up more Yazidi territory, the Yazidis are being forced to convert, face execution, or flee. "Our entire religion is being wiped off the face of the earth," warned Yazidi leader Vian Dakhil.

While the advance of the militants constitutes a grave threat to Yazidis, persecution has been a painful historical constant for the small religious community almost since its formation. "This dilemma to convert or die is not new," says Christine Allison, an expert on Yazidism at Exeter University.

A MISUNDERSTOOD RELIGION

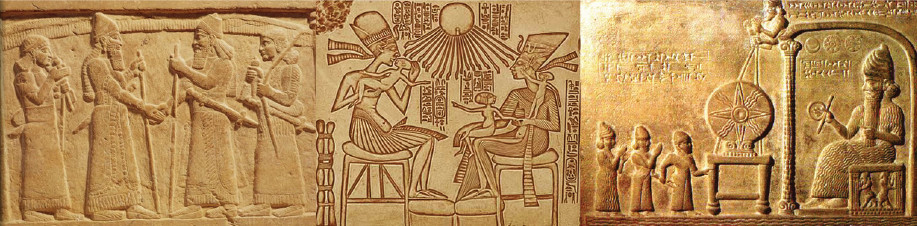

The Yazidi religion is often misunderstood, as it does not fit neatly into Iraq's sectarian mosaic. Most Yazidis are Kurdish speakers, and while the majority consider themselves ethnically Kurdish, Yazidis are religiously distinct from Iraq's predominantly Sunni Kurdish population. Yazidism is an ancient faith, with a rich oral tradition that integrates some Islamic beliefs with elements of Zoroastrianism, the ancient Persian religion, and Mithraism, a mystery religion originating in the Eastern Mediterranean.

This combining of various belief systems, known religiously as syncretism, was what part of what branded them as heretics among Muslims. While some Yazidi practices resemble those of Islam—refraining from eating pork, for example—many Yazidi practices appear to be unique in the region. Yazidi society is organized into a rigid religious caste system, and many Yazidis believe that the soul is reincarnated after death. While its exact origins are a matter of dispute, some scholars believe that Yazidism was formed when the Sufi leader Adi ibn Musafir settled in Kurdistan in the 12th century and founded a community that mixed elements of Islam with local pre-Islamic beliefs.

Yazidis began to face accusations of devil worship from Muslims beginning in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. While the Yazidis believe in one god, a central figure in their faith is Tawusî Melek, an angel who defies God and serves as an intermediary between man and the divine. To Muslims, the Yazidi account of Tawusî Melek often sounds like the Quranic rendering of Shaytan—the devil—even though Tawusî Melek is a force for good in the Yazidi religion.

"To this day, many Muslims consider them to be devil worshipers," says Thomas Schmidinger, an expert on Kurdish politics the University of Vienna. "So in the face of religious persecution, Yazidis have concentrated in strongholds located in remote mountain regions," he adds.

The Yazidis are not the only religious minority threatened by the Islamic State. Thousands of Christians have fled Mosul since the extremists captured the city in early June. For now, religious minorities are finding refuge in Kurdish territory in the north. But the Islamic State is capturing villages just a few miles from the Kurdish capital of Erbil. With the security of Kurdish territory in doubt, the U.S. launched air strikes on Islamic State positions late last week.

Organized anti-Yazidi violence dates back to the Ottoman Empire. In the second half of the 19th century, Yazidis were targeted by both Ottoman and local Kurdish leaders, and subjected to brutal campaigns of religious violence. "Yazidis often say they have been the victim of 72 previous genocides, or attempts at annihilation," says Matthew Barber, a scholar of Yazidi history at the University of Chicago who is in Dohuk interviewing Yazidi refugees. "Memory of persecution is a core component of their identity," he says.

Isolated geographically, and accustomed to discrimination, the Yazidis forged an insular culture. Iraq's Yazidis rarely intermarry with other Kurds, and they do not accept religious converts. "They became a closed community," explains Khanna Omarkhali, of the University of Göettingen.

VICTIMS OF HUSSEIN'S REGIME

Yet, as Kurdish speakers, Yazidis often share the same political fate as Iraq's other Kurds. In the late 1970s, Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein launched brutal Arabization campaigns against the Kurds in the north. He razed traditional Yazidi villages, and forced the Yazidis to settle in urban centers, disrupting their rural way of life. Hussein constructed the town of Sinjar, and forced the Yazidis to abandon their mountain villages and relocate in the city.

After the United States toppled Hussein in 2003, Iraqi Kurds were given an autonomous region in northern Iraq known as the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG). But Sinjar, along with many border regions at the edge of the KRG, remains an area of dispute between the Kurds and the government in Baghdad. The KRG claims Sinjar as Kurdish, while Baghdad still considers the area under its control.

As ISIL sweeps through the Yazidi homeland, Kurds throughout the region are rallying to defend the embattled religious minority. This week, Kurdish fighters from Syria and Turkey crossed into Iraq and joined with the KRG to push back ISIL and secure a safe passage for the Yazidis out of Sinjar. Some Yazidis are even fleeing into war-torn Syria, seeking the protection of Syrian Kurds in the north.

For now, these Kurdish fighters are the only thing standing between the Yazidis and the Islamic State. As he has continued his work with Yazadi refugees, Matthew Barber says that a general panic has set in as hundreds of thousands of new arrivals from western Iraq flood Yazidi villages outside Dohuk, seeking shelter behind Iraqi Kurdish lines. "The Yazidis are terrorized," he says. Refugees are now calling the mass exodus from Sinjar the 73rd attempt at genocide.

With the help of U.S. air support, the Kurds vowed to retake Sinjar in the coming days. For the Yazidis the stakes are especially high. "It's difficult to see how Yazidism could exist if they all left northern Iraq," says Allison. "The struggle is truly existential."

Источник: news.nationalgeographic.com