Articles

Yazidi minority refugees worry about the future of their culture

Simon Albaugh / 4 августа 2017 года

Scaramagkas Refugee Camp, Greece) — Mahamud Murad and his family live in a small caravan under the shadow of shipping containers and barbed wire fences. His family, and the many others like his were placed at the far end of the Scaramagkas refugee camp for the groups safety. Still this hasn’t prevented numerous knife attacks.

Now, in his humble home, Mahamud and his family wait until they can finally relocate to the prize of every refugee in Greece: Germany. But even though this would be cause for celebration, this is not what they truly want.

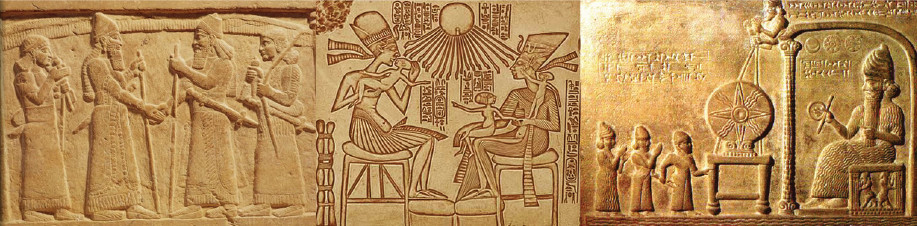

For one thing, Mahamud’s daughter is still missing. And for another, their culture that is thousands of years in the making – supposedly older than Judaism and Zoroastrianism, with ties to ancient Mesopotamia – is in peril. Their culture, the culture of Yazidism, may not survive.

The Yazidi’s religion depends heavily on the members being together. This used to be in the Shengal region of Northern Iraq. But after multiple forces drove the vast majority of Yazidis out of their sacred land, the population is now scattered across the Middle East and Europe.

There are approximately 700,000 surviving Yazidis today. 500,000 were removed from their homes and are now living as refugees in improvised refugee camps. 4,000, according to Mahamud, are refugees in Greece.

Mahamud said there are around 400 Yazidi in the Scaramagkas refugee camp. Some are going to Germany, but many are either going elsewhere or not yet promised to even leave the camp.

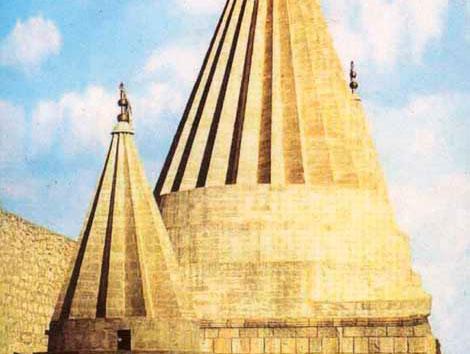

Yazidi are a Kurdish-speaking religious group from Northern Iraq. Instead of the Judeochristian God, they worship a forgiven dissenter as a symbol of God’s benevolence. This fallen angel, named Melek Taus, or the Peacock angel, follows a similar mythological story to the Christian Satan and Muslim Shayton.

Their religion is the product of relative isolation from most of the world. Western culture first heard of their existence in 1849, despite the notion that some believe this religion is, at highest estimate, 12,000 years in the making.

This religion is especially endangered because of its endogamous laws. If one marries outside the religion, they are considered to have converted to the religion of their spouse. Yazidi do not accept outside converts to their religion.

When this is paired with the relatively peaceful nature of their religion, they became an easy target for ISIS, known in Iraq under its Arabic acronym, Daesh.

One of the most difficult factors in this problem is the trauma that many refugees must hold as they try to continue with their lives.

Achmed Saleh, an unaccompanied minor from Sinjar and a Yazidi, also stays in Scaramagkas refugee camp. He is still awaiting approval for asylum and risks being sent to Turkey like other Yazidi before him, where safety is not guaranteed.

“So difficult for Yazidi,” Saleh said. “Many people, Yazidi men, girls, they [ISIS] kill everyone. Small kids… I don’t know why.”

Many have compared what is happening to them to a contemporary Holocaust. It was a result of ISIS spiritual leader Turki al-Binali’s Fatwa, or religious commandment, that the ninevah province of Northern Iraq in which the Yazidi primarily live has been the target of systematic killings of men and children. While the women, some as young as 9 years old, are being sold in ISIS sex slave markets.

In Mahamud and Achmed’s home of Shengal, or in English Sinjar, few have returned. One of the foremost scholars on the Yazidi religion believe that this is the difference between the culture’s survival and its end.

“The Sinjar Region is now free of IS [Islamic State] but the people, who should be helped to return to rebuild their homes and lives, are instead continuing to live in camps, afraid to return amid the political conflict in the area,” said former Executive Director of Yazda Relief Organization Matthew Barber in a written statement.

“In this situation, Yazidis continue to leave the country, feeling powerless to determine the course of their own homeland and hopeless regarding the prospect of rebuilding their lives in their own lands. This is very dangerous because Yazidi tradition is closely connected to sacred places in the land, and it remains to be seen whether Yazidi religion will be able to survive in diaspora.”

Yazidi feel this ominous threat from all corners of their separation.

“We don’t want the money or anything,” Mahamud said, with his nephew Khter Murad translating. “Just to save. To save the Yazidi people. We want to live like any people. Save anyone.”

In that small caravan, next to barbed-wire fence and precariously stacked shipping containers, there is a small group that is not only scared or traumatized, but desperate. They are clinging to their way of life, their beliefs, and their culture in a world that will never be the same for them.

Источник: ourefugeereport.com