Articles

Were 'Devil Worshipper' Yazidis There for the Birth of Human Culture?

Michael Smith / 2 сентября 2014 года

As the rolling news reports the latest round of atrocities in the ongoing Iraqi catastrophe, it’s easy to be desensitized to the desperate situation engulfing the Yazidis.

An entire people forced to abandon their ancestral homeland with only the shirts on their backs, they’re making the gruelling and perilous trek to refugee camps in Kurdistan, on foot through mountains and along desert dirt tracks. Many weren’t fortunate enough to escape mass executions at the hands of Islamic State militants, and thousands are still trapped up Mt. Sinjar in the baking heat with no food, water or shelter. Children and the elderly are dying in their droves.

In the eyes of IS, the Yazidis are Devil worshippers—something that’s actually kind of tricky to argue against; the group consider themselves to be the chosen people of Melek Taus, the “Peacock Angel," who they also know as Shaitan, or Satan. In Yazidi tradition, this special relationship began when Shaitan visited their ancestor Adam in the garden of Eden, bearing forbidden fruit.

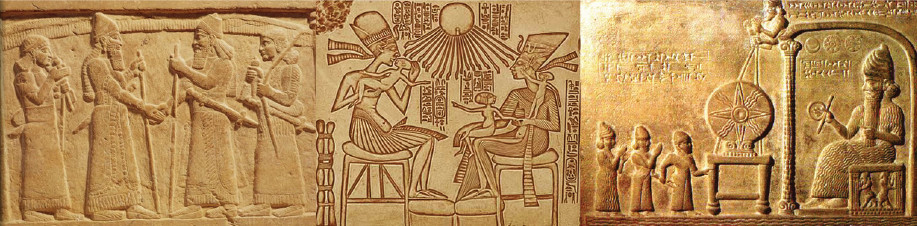

The Yazidis are an ancient rural people from the plain of Mesopotamia, the cradle of civilization. Almost forgotten archaeological layers of belief still poke through the surface here, old echoes that stretch religious absolutes held sacred by Muslims, Christians and Jews alike into weird, unsettling shapes.

The parallels between the Peacock Angel and the Satan we’re more familiar with can be baffling—Melek Taus is God’s most important angel, his commander-in-chief in this world, which was also his original role in the Abrahamic traditions. He’s also a fallen angel who rebelled against God and was subsequently cast into Hell; but in the Yazidi cosmology, after 40,000 years his tears quenched Hell’s flames and God forgave and reinstated him.

This hints at the complex, ambiguous, almost human quality of Melek Taus. In the Mishefa Re, the holy book the Yazidis believe to be his revealed word, he tells us: “I give and take away; I enrich and impoverish; I cause both happiness and misery ... All treasures and hidden things are known to me; and as I desire, I take them from one and bestow them upon another.”

The Yazidis don’t see good and evil as polar opposites personified in particular gods, but as qualities that are integral parts of creation—they exist throughout the world, within the mind and spirit of human beings, and also within the Peacock Angel. The path we choose is up to us. “I allow everyone to follow the dictates of his own nature, but he that opposes me will regret it sorely.”

One of Melek Taus’ symbols is fire, and he can illuminate as well as burn. He’s responsible for granting mankind knowledge and free will, and in an intriguing twist on the familiar Garden of Eden story, he first initiates Adam with forbidden fruit: “[God] commanded Gabriel to escort Adam into Paradise, and to tell him that he could eat from all the trees, but not of wheat. Here Adam remained for a hundred years […] Melek Taus visited Adam and said, ‘Have you eaten of the grain?’ He answered, ‘No, God forbade me.’ Melek Taus replied and said, ‘Eat of the grain and all shall go better with thee.’”

The Yazidis claim to be the world’s oldest nation, tracing the origin of their culture back to this covenant between Shaitan and Adam. Though this obviously has the ring of massive over-simplification and elaboration common to all origin myths, there’s a growing body of archaeological evidence that seems to suggest there’s an element of symbolic truth in it—that the Garden of Eden story shared by all the Middle Eastern religions might in fact be a faded folk memory of how human civilization began in the first place, a memory connected to the Yazidis in a very special way; a memory that Judaism, and subsequently Christianity and Islam, inherited from them, distorting it in the process.

You can’t convert or intermarry into Yazidism. They’re a people set apart, a distinct ethnic group who’ve always lived in a corner of the Turkey-Iraq borderland that folk memory across the wider region recalls as the location of the Garden of Eden. All very well, you might say—the Garden of Eden’s just a myth. But have you heard of Gobekli Tepe? It’s a recently unearthed archaeological site just over the Turkish side of the border that’s in the process of causing complete upheaval to all our old assumptions about the dawn of human civilization.

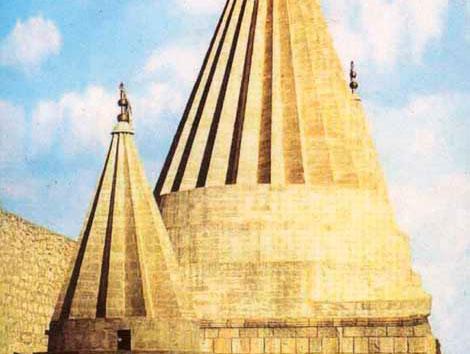

The discovery of Gobekli Tepe came when an archaeological team noticed a curious collection of what looked like gravestones on top of a strangely isolated hill. They began to examine these graves, which they soon discovered were just the tip of an astonishing iceberg: that the “hill” was in fact man-made, and, more importantly, that the “graves” were just the tops of huge, immaculately preserved limestone megaliths. These giant stones formed a large circular sacred site that had mysteriously been buried under tons of earth in distant antiquity, the rocks adorned with beautiful carvings of snakes, boars and strange bird-gods that the Yazidi swear they easily and instantly recognise as depictions of Melek Taus and their other angels.

To say these bird-gods have come down to us from the dawn of time is, in human terms, no exaggeration. The obvious comparison is with Stonehenge, but the real shock about Gobekli Tepe is its almost unimaginable age. Stonehenge is about 4,000 years old. Gobekli Tepe has been carbon dated and clocks in at an unbelievable 12,000 years old, extending the advent of monumental human architecture—and with it a human society large and complicated enough to build it—at least three times further back into the deep past, a time before writing, before metal and also a time before farming. “Stone age” hunter-gatherers built this place. Until very recently we imagined complex society—“civilization”—began with agriculture. Gobekli Tepe overturns this assumption about the birth of human culture in a stroke.

But the significance of Gobekli Tepe doesn’t stop there. Agriculture seems to have started around this area, too, around 10,000 years ago, when the megaliths were already 2,000 years old. Pigs were first domesticated in a place called Cayonu a few miles away. The wheat species first domesticated in ancient European and Asian agriculture all descended from a common ancestor: “einkorn” wheat, which just happens to be the very same indigenous species of these ancestral Yazidi heartlands. Which makes the small detail of Satan bringing Adam knowledge by introducing him to grain rather than apples in the Yazidi version of the Eden story suddenly seem very significant.

So, the Yazidis are descended from the original inhabitants of the garden of Eden and worship a bird-god called Satan, who brought mankind out of the Stone Age with the forbidden fruit of agriculture, right? Who knows.

This baffling conundrum certainly poses intriguing questions about how far back into the dawn of human culture—into the “Stone Age” and its transition into “civilization”—all our familiar stories about God and the Devil and Adam and Eden actually go. It also paints the Devil in a newly sympathetic light, and you wonder if the Old Testament’s take on Satan might have been a hatchet job on the older rival religion’s god.

It must be completely obvious to anyone who’s grown up with the “War On Terror” that the first thing you do in such situations is paint the other guys—and their Gods—as evil, blood-thirsty war mongers, because by demonizing them you can justify any inhumanity you might subsequently commit. It was the basic technique of Bin Laden and of Bush, and it seems perfectly tenable to imagine the writers of the New Testament involved in similar smoke and mirrors.

This would certainly be typical of the Yazidi’s historical experience; there have been 73 attempted genocides of these “devil worshippers” since the arrival of Islam in the region. The most remarkable part of the whole story is that the Yazidis have even survived at all.

Источник: www.vice.com